February 17, 2026

Salk Institute scientists show how proteins regulate our genome’s 3D shape to influence gene expression and cell identity

Salk Institute scientists show how proteins regulate our genome’s 3D shape to influence gene expression and cell identity

LA JOLLA—How does our DNA store the massive amount of information needed to build a human being? And what happens when it’s stored incorrectly? Jesse Dixon, MD, PhD, has spent years studying the way this genome is folded in 3D space—knowing that dysfunctional folding can cause cancers and developmental disorders, including autism-related disorders. The latest research from his lab adds to a growing understanding that the genome’s 3D organization is constantly in flux. Using different types of human cells, his lab showed that this dynamic genome unfolding and refolding process occurs at different rates in different parts of the genome, which, in turn, influences gene regulation and expression.

The study, published in Nature Genetics on February 16, 2026, and funded by both federal research grants and private philanthropy, may point to targets for blocking the dysfunctional folding that leads to cancers and developmental disorders.

“There are six billion base pairs in your genome, and in the last decade we’ve been learning about the molecular machines that fold and organize that massive amount of information,” says Dixon, senior author of the study and associate professor and holder of the Helen McLoraine Developmental Chair at Salk. “What’s interesting is that this folding doesn’t just happen once and then the genome stays put—it seems to be constantly unfolding and refolding. Our study gives us a better idea of where and how often the genome is doing this, which ultimately adds to our understanding of those molecular machines, and, in turn, what may be going on when they dysfunction during cancers or developmental disorders.”

Each human cell contains two meters of DNA—critical code that brings every protein, structure, and cellular process to life. Within that DNA code are tens of thousands of genes, which are short stretches of code that can be used to regulate or produce proteins.

This crucial information must be stored and organized in such a way that it can fit inside a cell’s nucleus and move around to change gene accessibility and be strategically maneuvered to bring together regions that need to interact but that are relatively far apart. Cells have cleverly found a way to knock out all three of these needs at once: loops! Loops are tightly mediated by a protein complex called cohesin, which works alongside an accessory protein, NIPBL, that helps cohesin move along DNA to form these loops.

Recent studies have shown that these cohesin-mediated loops are constantly forming and disassembling. This new understanding of genome folding as a dynamic process inspired a host of new questions: How often is DNA looping and un-looping? Is every part of the genome equally dynamic? What role is NIPBL playing in this movement?

“Current data around the spatial organization of the genome suggest that genome folding has little impact on gene expression—but we thought, perhaps we just aren’t looking at it in the right way,” says first author Tessa Popay, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in Dixon’s lab. “By specifically disrupting folding dynamics, we were able to identify the aspects of spatial genome organization that contribute to gene regulation and expression.”

The Salk team first depleted NIPBL in immortalized human retinal pigment epithelial (RPE-1) cells to see what impact that would have on loop dynamics. Without NIPBL, cohesin could no longer efficiently move along DNA and form loops. Unable to create new loops, the genomes unfolded—but not uniformly. Rather, some regions of the genome unfolded relatively quickly, while others did so over the course of many hours.

Curiously, the relative stability of different genome areas appeared to be related to functional differences. Loops that were forming and unraveling over many hours were associated with silent genome regions—stretches of the DNA where the genes weren’t in use. Loops that turned over more quickly were associated with expressed genome regions—places where genes were in high use and coordinating cell type-specific functions.

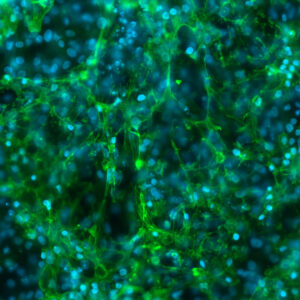

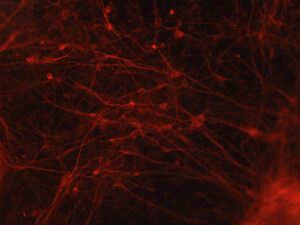

Wondering whether these dynamics may indeed influence gene expression and cell identity, the researchers moved into heart cells and neurons, deriving these from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). They demonstrated that this dynamic organization is most important in heart cells at genes related to heart cell function and in neurons at genes related to neuronal cell function. These heart-function and neuronal-function genes are, of course, in different places in the genome—this flexibility in genome folding likely helps cell types achieve and maintain their distinct identities.

“One thing this appears to suggest is that the continuous folding and unfolding of our genome may be particularly important for helping a cell ‘remember’ who it is supposed to be by preserving expression of genes that are unique to different cell types,” says Popay.

The researchers have a few theories as to why areas of the genome related to identity seem to be the most active. Their best guess is that the constant reiteration of these loops makes identity stronger, by repeatedly creating fresh connections between genes—like the cell is constantly giving itself a pep talk, reading its affirmations in the form of proteins it needs to create to maintain its function.

Though the findings lead to new mysteries, Dixon says what they know now helps explain the symptoms associated with dysfunctional genome folding in humans.

“These genome folding machineries tightly control cell identity in every cell, so it actually makes a lot of sense that when we see mutations in them, we get these syndromic conditions like Cornelia de Lange syndrome that impact different parts of the body in different ways,” says Dixon. “And cancer is potentially exploiting that same principle, changing where in the genome these dynamics are more important to manipulate cell identity and encourage uncontrolled growth.”

With this new confirmation that the genome’s dynamic 3D structure significantly impacts gene expression, scientists can now connect the dots between genome structure and disease and begin imagining new therapies for cancers and developmental disorders. Foundational research means widespread impact—especially when it comes to the building blocks for life.

Other authors include Ami Pant, Femke Munting, Morgan Black, and Nicholas Haghani of Salk and Melodi Tastemel of UC San Diego.

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (U01-CA260700, S10-OD023689, S10-OD034268, P30-CA014195, P30-AG068635, P01-AG073084-04, P30-AG062429), Salk Excellerators Fellowship, Rita Allen Foundation, Pew Charitable Trusts, Howard and Maryam Newman Family Foundation, Helmsley Charitable Trust, Chapman Foundation, Waitt Foundation, American Heart Association Allen Initiative, and California Institute for Regenerative Medicine.

DOI: 10.1038/s41588-026-02516-y

JOURNAL

Nature Genetics

AUTHORS

Tessa M. Popay, Ami Pant, Femke Munting, Melodi Tastemel, Morgan E. Black, Nicholas Haghani, Jesse R. Dixon

Office of Communications

Tel: (858) 453-4100

press@salk.edu

The Salk Institute is an independent, nonprofit research institute founded in 1960 by Jonas Salk, developer of the first safe and effective polio vaccine. The Institute’s mission is to drive foundational, collaborative, risk-taking research that addresses society’s most pressing challenges, including cancer, Alzheimer’s, and insufficient agricultural resilience. This foundational science underpins all translational efforts, generating insights that enable new medicines and innovations worldwide.