00;00;06;06 – 00;01;00;21

VO Victoria

Welcome to Beyond Lab Walls, a podcast from the Salk Institute. Join hosts Isabella Davis and Nicole Mlynaryk on a journey behind the scenes of the renowned research institute in San Diego, California. We’re taking you inside the lab to hear the latest discoveries in cutting edge neuroscience, plant biology, cancer, aging, and more. Explore the fascinating world of science while listening to the stories of the brilliant minds behind it. Here at Salk, we’re unlocking the secrets of life itself and sharing them beyond lab walls.

00;01;00;23 – 00;01;31;28

Isabella

Hi everyone, and welcome to Beyond Lab Walls. I’m Isabella, and today I’m really excited to sit down with Professor Tony Hunter. Tony is a cancer biologist, but that happened kind of accidentally. His real interest has always been in the basics, exploring the intricate programing and regulation of the proteins and molecules that rule our cellular world. His dedication to the basics has led to some incredible discoveries about cancer biology, which have been used to develop therapeutics that help real patients fight cancer every day.

00;01;32;01 – 00;01;45;09

Isabella

This year is Tony’s 50th year at the Salk Institute, so we have quite a legacy to cover today. I’m going to go ahead and jump in at the very beginning. Hi, Tony. Welcome. Where do you grow up and were you always interested in science?

00;01;45;11 – 00;02;14;05

Tony

So I grew up in Kent, in the southeast corner of England, near Canterbury. I wouldn’t say I was always interested in science. My dad was an MD. He was a surgeon at a local hospital. My grandfather was a dentist. So there was sort of medical science in in the family. But I wasn’t really deeply passionate about science, and it wasn’t really until I was sent away to a boarding school in Essex at the age of 13, where I sort of developed an interest in science.

00;02;14;08 – 00;02;43;18

Tony

In fact, there’s a funny story that when I got there, there were– I was put in the lowest possible grade. Within two weeks, it was decided I needed to move up a grade. And so the headmaster called my father and said, “Tony’s got to be moved a grade. Should he specialize in science or in the humanities?” And the decision was made without my consent, that I should specialize in, in the science classes.

00;02;43;18 – 00;03;04;23

Tony

And so from the age of 13, really, my career was set. When I graduated from high school, or public school in that case, and went up to Cambridge for my bachelor’s degree. I focused on all natural sciences, as they were called, and particularly specializing in biochemistry in my final year.

00;03;04;26 – 00;03;29;19

Isabella

So I know that Oxford and Cambridge have a unique teaching style. In addition to normal lectures, you meet with an advisor to talk through what you know and what you’ve learned on a weekly or biweekly basis in very small groups. And on top of that, of course, you sit exams and all of that like a normal student. But science homework can be written instead of in pop quiz form or in worksheet form.

00;03;29;21 – 00;03;46;00

Isabella

I’m curious, in retrospect, do you think that intimate style and the emphasis on written and spoken explanations of your science shaped the way that you do science and your desire to come to Salk, which is another place that similarly emphasizes relationships and collaboration?

00;03;46;02 – 00;04;11;06

Tony

Well, I’m sure it had a big effect on my development as a scientist. Yes, in Cambridge they’re called supervisions and not tutorials. And so for each subject you have a supervisor who you meet once a week, I think it was, maybe less, and talk about the lectures you’ve just been listening to. And a supervisor could fill in some details and explain some things you didn’t understand.

00;04;11;08 – 00;04;41;24

Tony

So I had some some very influential supervisors who went on to become very eminent scientists. And then in turn, when I graduated with my bachelor’s degree in 1965 and became a graduate student, I then took on the role as a supervisor. And some of the people I supervised have gone on to be very influential. And in fact, one of them went on to become the director of the famous Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge, where Francis Crick and Sydney Brenner and Aaron Klug were.

00;04;41;26 – 00;04;50;09

Isabella

Yeah, there’s Salk connection there.

00;04;50;12 – 00;04;58;07

Isabella

So you were studying biochemistry at Cambridge. You worked your way up to supervising. When did you pivot to cancer biology?

00;04;58;09 – 00;05;29;09

Tony

Well, that took a long time, actually. I was really trained as a pseudo molecular biologist. So in the mid-sixties, when I started my graduate work, the genetic code had not yet been fully worked out. I mean we knew DNA encoded proteins. And we knew a little bit about messenger RNA, but the genetic code was still being worked out and couldn’t do any of the things we take for granted now, like sequencing DNA or sequencing proteins, etc.

00;05;29;12 – 00;05;59;09

Tony

So I was interested in how proteins are made in cells, and that was what my graduate thesis work was on. And then when I got my PhD in 1969, I remained in Cambridge, as a college fellow. But in 1969, right after I got my PhD, I married a fellow graduate student, Pippa Marrack, and she was training as an immunologist a couple of years behind me, and she decided she wanted to do a postdoc in San Diego at UCSD.

00;05;59;10 – 00;06;19;24

Tony

And so I had to find a place to work in La Jolla for a couple of years, while she did her postdoc. Luckily, her advisor knew Walter Eckhart and I met up with Walter at a meeting at the Royal Society and in London, and I went up to him and said, now would you take me on as a postdoc?

00;06;19;24 – 00;06;52;13

Tony

And he said, yes. I hadn’t realized really at the time that he hadn’t had any postdocs. He was just a new assistant professor. It wasn’t, he wasn’t called an assistant professor, they were members, I think they were called. So I became actually, in the end, his second postdoc. And we arrived here in October of 1971. And this huge social change from being in rather formal and proper Cambridge.

00;06;52;15 – 00;07;12;07

Tony

To the very relaxed Californian lifestyle.

00;07;12;10 – 00;07;39;04

Tony

But Walter’s lab was working on a, on a DNA tumor virus, polyoma virus, a small circular genome virus, and trying to use it as a model to understand potentially the basis of human cancer. And so I started working on polyoma virus, thinking it would be temporary and I would go back to Cambridge, finish my fellowship, and and get a job working on protein synthesis, probably.

00;07;39;06 – 00;08;05;11

Tony

And then I did go back. Pippa and I split up, she, she got a job, in the US with, another partner. And I went back to Cambridge to look for a job, which I applied to a couple of, institutions, and neither of them wanted me. So I was working in the Department of Biochemistry in Cambridge, where I got my PhD and was working as a research fellow.

00;08;05;14 – 00;08;42;08

Tony

So I applied to them because they had an open position, junior position. And I also applied to the Imperial Cancer Research Fund, which was a cancer research institution in London, in Lincoln’s Inn Field. And Renato Dulbecco, who had been one of the founding fellows of the Institute, he was the first fellow to arrive and start work in the temporary buildings, and then moved into the third floor of the North Building in 1966, when the building opened, and he he was married to Maureen Dulbecco, with whom he had had a child, Fiona.

00;08;42;11 – 00;09;10;01

Tony

And I think they decided that they would like to bring up their child in the UK. And so in 1972, Renato left the Institute, became the vice director of Imperial Cancer Research. And so I wrote to him when I got back in 1973 and said, “Dear Renato, do you have a position for me?” And I got this letter back that said “Dear Tony, thank you for your inquiry about the position.

00;09;10;03 – 00;09;35;07

Tony

I regret to say that we already have enough molecular biologists.” Course they didn’t really have any molecular biologists, but that was his excuse. But his leaving the Institute created half a floor of empty space, because every fellow had 8000ft². And there weren’t any junior faculty at that time to work in the general area of, tumor virology and cancer research.

00;09;35;07 – 00;10;00;17

Tony

And before I went back to the UK, Walter had offered me a position as one of these junior faculty members, an assistant professor, and I had to turn him down because I thought I would go back to the UK and get a job there. But when that didn’t materialize, I, I called up Walter, I wrote to him, I forget now what I did but, and asked him whether the job was still open and he said he said yes.

00;10;00;19 – 00;10;08;03

Tony

Much to my relief.

00;10;08;06 – 00;10;37;16

Tony

So I came back in 1975. I had to wait for a while. I think I got the job offer in May of ’74, but I couldn’t come back until I got a green card, and my green card was delayed because the local– I had to be a local police report as part of my dossier to, I guess, ensure that I hadn’t been arrested or done anything illegal.

00;10;37;19 – 00;10;48;15

Tony

And so it took about six months before I actually left the UK. During that time, we managed to burn the lab down. There was no sprinkler system and no one else–

00;10;48;17 – 00;10;50;29

Isabella

How did the fire start?

00;10;51;02 – 00;11;19;01

Tony

The official verdict is it was an ether wash bottle in a refrigerator that had been sparked by internal thermostat. My version is that I think it was a water bath over one of the cup sinks in the lab, because we used to use ether for extracting TCA and then pour it down the sink. And so there was a layer of ether on the water remaining in the, in the drain.

00;11;19;03 – 00;11;33;18

Tony

And when I went into the lab around, I don’t know, 10:30 that night, I could smell ether in the air because it was an unusually warm June evening. And, either way, it burned. And burned for several hours.

00;11;33;20 – 00;11;38;22

Isabella

And Salk didn’t see that as a red flag that you might burn down one of their labs?

00;11;38;24 – 00;11;44;02

Tony

Well, I guess it could have been, but actually, the offer was made before we burned down the lab. So.

00;11;44;04 – 00;11;51;10

Isabella

So outside of having no other choice since your Cambridge lab burnt to a crisp, were there other factors that pulled you back to Salk?

00;11;51;13 – 00;12;22;15

Tony

Well, one of the motivations for coming back was that we had started river rafting. I was a postdoc. Bill Kogan, a graduate student in the lab, had done a rafting trip in 1971 with some friends, and he decided this was such fun–they rafted the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon–that he would organize a trip for the summer of 1972. And he asked whether we’d like to come and we didn’t really know what we were letting ourselves in for, but we agreed.

00;12;22;17 – 00;12;49;04

Tony

And so we met up with this rather chaotic trip that had all sorts of equipment problems, etc. The next two weeks we rafted down the river, going through all these wild rapids and flipping some boats, etc. and the day I hiked down was the last day I shaved. So that was July the 13th, 1972. So I have not shaved once since then.

00;12;49;11 – 00;12;51;21

Isabella

Wow. To this day.

00;12;51;24 – 00;13;19;08

Tony

The 70s, people were growing out, growing their hair long. And there’s another funny story about long hair. So my hair– I’d actually grown a little bit in Cambridge, but it was quite long. We used to go camping in the Baja Peninsula as opposed to the– the Mexican border agents were trying to, I think, prevent drugs, particularly marijuana at the time, from coming into the US.

00;13;19;08 – 00;13;43;21

Tony

And so they would check people going down to see if that’s what they were potentially planning to do. And so knowing that I’d bought a wig to tuck my hair under. So I looked like I was relatively short hair, even though I, I had a, I had a beard. And so we went, we drove, were driving through Tecate, which is a much smaller border crossing.

00;13;43;21 – 00;14;04;21

Tony

And the agent there, I drove up and he looked at me and he reached over and whipped the wig off my head. And so we couldn’t cross there. So we turned around, and then we were a group of 3 or 4 cars, and I was put in the back of another car with my hair pinned up with a couple of kids in it, and we got through in Mexicali instead.

00;14;04;21 – 00;14;10;16

Tony

So and so that was suddenly all of this was clearly, you know, influential in my decision to come back.

00;14;10;16 – 00;14;25;28

Isabella

From Cambridge gowns and traditions to wild rapids and having a wig snatched off your head by a border agent. Wild transition. It seems like you adapted to the California lifestyle really quickly at this point in your life, do you still feel British?

00;14;26;01 – 00;14;54;07

Tony

I have, yes. I left the UK for good when I was 31, I guess. Is that right? Yeah. 31. And so obviously, yes, I spent more of my life here. I still think of myself as British, I think although I’m a U.S. citizen, a dual citizen.

00;14;54;09 – 00;15;01;08

Isabella

So you have these adventures. You make it back to San Diego. You set up your lab. What are you working on?

00;15;01;10 – 00;15;24;18

Tony

I came back into the same lab space where I have been as a postdoc. Next, right next door to to Walter. We continue to collaborate. Francke and I published about 7 or 8 papers as Hunter and Francke, Francke and Hunter, based on the work we done as postdocs and Walter’s name wasn’t on the papers, and I just think we acknowledged him for providing support.

00;15;24;20 – 00;15;53;24

Tony

You know, it had been a great collaboration, and I’ve learned everything from him about polyoma virus. And so when I came back, it was natural I was, would have to switch to back to working on polyoma virus and there was funding available. In fact, while I was in back in the UK waiting for my green card, I had written my first grant application to to study DNA replication that I had been working on as a postdoc and got that funding.

00;15;53;24 – 00;16;18;15

Tony

And so I, I was sort of obliged, I think, to do cancer research. In the interim, in the year and a half that I was back in England, quite a lot of progress had been made in understanding the polyoma virus genome, and so one could begin to decode the proteins that were made by the virus. And the key, obviously, to understanding how the polyoma virus causes tumors is to know what proteins it makes.

00;16;18;15 – 00;16;41;29

Tony

The virus has two halves. One half makes the coat proteins that package the DNA, and they’re clearly unlikely to be involved in how the virus transform cells into cancer cells. And the other half of the virus we call the early region, because it’s the part that’s that’s transcribed into RNA and translated that when the virus enters the cell, we could deduce two lines of evidence.

00;16;41;29 – 00;17;06;25

Tony

One was we had antibodies that pull down proteins from the infected cells that we call tumor antigens or T antigens. And there were three of them. And we could deduce from that DNA sequence how they were made. So that was occupied the first 2 or 3 years of what I was doing when I came back and set up a lab, was to try and figure out how these proteins are made, which of them are most important for making a cancer cell.

00;17;06;28 – 00;17;11;02

Isabella

You really were digging into the cancer biology then at that point.

00;17;11;04 – 00;17;38;12

Tony

I continued a little bit of work on tobacco mosaic virus, and that was the collaboration we set up in Cambridge. After the fire, there was a group working on the structure of tobacco mosaic virus, and the puzzle was how this RNA, it’s an RNA virus. It packages a messenger RNA. So its RNA is translatable. When you took the RNA and put it in one of these cell free translation systems, it does not make the coat proteins.

00;17;38;12 – 00;18;03;28

Tony

So this was a big puzzle. We knew the RNA encoded the coat protein based on some mutation studies, but it didn’t make it. And Tim Hunt and I–Tim was a fellow graduate student in Cambridge, he went on to win the Nobel Prize for his work on a cell cycle–figured out that the virus might somehow make a smaller RNA that makes the coat protein, and that’s what we discovered.

00;18;04;01 – 00;18;16;21

Isabella

It’s incredible how technique has advanced so much in such a short amount of time, especially when you’re looking at RNA and DNA, where sequencing a genome was not too long ago this giant puzzle that took enormous effort.

00;18;16;24 – 00;18;34;15

Tony

The human genome, you know, was sequenced only 25 years ago now. And it took just a huge amount of effort, billions of dollars. Now you can do it in a few hours on one of these machines.

00;18;34;18 – 00;18;56;24

Isabella

So you’re learning more about how tumors form. And along comes this really iconic discovery of yours. I want to ask you to tell that story, but I want to also give our listeners a little context first. So the cellular world is run by proteins. Proteins determine everything from cell identity to specific cellular functions. And one way they do this is by sending signals.

00;18;56;27 – 00;19;19;05

Isabella

They can send signals within one cell, or they can send signals to other nearby cells to warn them of important news. But obviously they can’t always be sending messages. We want our proteins not crying wolf. Instead, cells have special ways of turning proteins on and off and regulating their activity. One of those ways is through the use of tyrosine kinases.

00;19;19;05 – 00;19;46;19

Isabella

Tyrosine kinases modify proteins by phosphorylating them, which means they attach phosphate molecules to them to regulate their activity. Tyrosine kinases specifically control proteins that help our cells grow and divide–two things we don’t want cancer cells to be able to do. Figuring out how tyrosine kinases work could help scientists control them in cancer or other diseases where we want cells to stop dividing.

00;19;46;21 – 00;19;51;15

Isabella

And that’s what Tony set out to do. I will let you tell the story now.

00;19;51;18 – 00;20;18;07

Tony

Once we’ve identified that one of the three polyoma virus encoded tumor antigens, middle T, was the main factor in through which the virus switches the cell into a tumor cell. Basically, it it drives the cell into the cell cycle so it can replicate, and that then continues on to become a tumor. We wanted to know how it did it.

00;20;18;10 – 00;20;52;18

Tony

And we really didn’t have any good ideas. But luckily, Ray Erikson’s group in Denver had shown that the transforming protein of rous sarcoma virus has an associated protein kinase activity, and their rationale was if you have a temperature sensitive mutant virus that only transforms cells at a low temperature, 36° centigrade, and then shift the cells to 41 degrees, the cells they go from a round transformed phenotype to a flat, normal phenotype. That happens extremely rapidly within 30 minutes.

00;20;52;18 – 00;21;20;24

Tony

If you now shift those cells back again to the permissive temperature within 30 minutes or so, they become transformed again. So they deduced that whatever was happening probably didn’t need some new RNA. And protein synthesis. It probably was happening on proteins already in the cell. We knew that phosphorylation was a way of changing protein activity. And so they tested the idea that maybe what was happening was the temperature shifts using antibodies to the SRC protein.

00;21;20;26 – 00;21;43;27

Tony

They showed it had a kinase activity. And of course, this was really dramatic and exciting. We immediately thought we should test whether polyoma virus proteins have this kinase activity. Much to my delight, we found there was a middle T antigen protein became phosphorylated in a in vitro kinase assay, where we pull down the proteins and then incubated them with gamma P32 labeled ATP.

00;21;43;27 – 00;22;16;25

Tony

And that led to the labeling of the middle T protein that wasn’t seen with mutant polyoma viruses that couldn’t transform cells. So that was that was an observation that was made by two other groups. We all attended the Cold Spring Harbor Symposium in the summer of 1979 and agreed to submit our papers to Cell, which was the up and coming journal, to published back to back to back. But the day after I had submitted the paper, I realized that one of the reviewers would probably ask what amino acid was getting phosphorylated.

00;22;16;25 – 00;22;43;10

Tony

And it turned out that that was tyrosine, which I had learned about in my biochemistry courses in Cambridge as the third hydroxy amino acid. And so eventually, by making some phosphotyrosine, we could establish that the middle T was phosphorylated on tyrosine. But then it was important that we were also working rous sarcoma virus, because Erikson’s group had reported that the SRC protein was a threonine kinase.

00;22;43;13 – 00;23;06;12

Tony

And so one day I was running the SRC protein as a control. And much to my amazement, it turned out that SRC was also phosphorylating tyrosine. And that Erikson had been misled by the fact that phosphotyrosine and phosphothreonine co-migrate at pH 1.9. And when I had done the original experiment, I had been too lazy to make a fresh 1.9 buffer.

00;23;06;12 – 00;23;26;12

Tony

And the pH had dropped point two of a pH unit and that allowed separation of phosphotyrosine and phosphothreonine. So. That’s the story in a nutshell.

00;23;26;14 – 00;23;46;17

Isabella

It’s so incredible the number of scientists and experiments it takes to come to a discovery like this. And today there are cancer drugs that target tyrosine phosphorylation. One of those is Gleevec, which is particularly effective in treating chronic myeloid leukemia, but is also effective against other cancer types. How does basic research turn into a therapeutic?

00;23;46;19 – 00;24;12;25

Tony

Well, that took a long time. I mean, the discovery that two viruses apparently were using tyrosine phosphorylation to drive cancer was a start, but that didn’t mean to say this was happening in human cancer. And that took a little while longer before people identified human cancer genes, and particularly, I would say, the BCR-ABL fusion gene that drives chronic myeloid leukemia

00;24;12;26 – 00;24;44;27

Tony

was really the first strong evidence that tyrosine phosphorylation was driving a human cancer, particularly a leukemia. But then through, you know, various strategies, people found other fusion proteins that involved a tyrosine kinase gene. And within about a year, we already knew there must be at least four human tyrosine kinase genes because different retroviruses are captured, different tyrosine kinase genes.

00;24;44;29 – 00;25;17;12

Tony

Then it became possible to do cloning using PCR-based strategies and that led to a whole new set of tyrosine kinases. So more and more tyrosine kinases are being identified. Evidence that some of these were transforming tyrosine kinases began to accumulate. And so within ten years, by, you know, 1990, we knew there were about 50 human tyrosine kinases, and about half of them have been implicated in cancer.

00;25;17;15 – 00;25;48;08

Tony

And so that led to the interest in developing potential small molecule or antibody inhibitors, because several of the tyrosine kinases that were implicated in cancer were receptor-like kinases. So they they were proteins that spanned the plasma membrane with an extracellular protein and an intracellular kinase part. And normally they’re regulated by binding a small protein ligand like epidermal growth factor.

00;25;48;11 – 00;26;18;00

Tony

But by being fuzed to another protein, they become activated through forming pairs or dimers of proteins. So that’s just how the ligands work. And so one can make antibodies against the external part of these proteins. So two real approaches. In fact, the first tyrosine kinase inhibitor drug to be approved was Herceptin, which is a monoclonal antibody that that blocks the activity of a receptor kinase called Her2.

00;26;18;00 – 00;26;46;08

Tony

So that was in 1998 I think that was approved. And then small molecule approach both in in academia but more importantly in industry at Ciba-Geigy that then became Novartis led ultimately to the development of Gleevec. So it took, you know, 20 something years. Now, things are greatly accelerated, everyone had to develop all the technology and the libraries and things develop the small molecule.

00;26;46;08 – 00;27;03;29

Tony

Now there, you know, something over 80 tyrosine kinase inhibitors that are approved. Many of them are targeting the same kinase. But they’re, they’re different because each company has to have a unique chemical entity to get it, get it patented, approved.

00;27;04;01 – 00;27;07;13

Isabella

How specific are these drugs to certain cancer types?

00;27;07;16 – 00;27;40;28

Tony

Well, each drug is targeted towards one specific tyrosine kinase. And so any any cancer that has a driver kinase of that type can be targeted by that small molecule drug. So it started with drugs that target leukemias. But now most solid tumors will have a potential TKI that can be used usually in combination. None of these TKIs, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, actually kill cells.

00;27;40;28 – 00;28;01;02

Tony

So they they put cells into stasis. And so you need a second drug like an immune checkpoint antibody, maybe, or another chemotherapeutic or a combination of kinase inhibitors to really kill the cells, which is what ultimately you need to do in order to get a cure.

00;28;01;04 – 00;28;14;00

Isabella

You’ve seen something leave your lab and turn into a real drug that changes patient lives. Does that experience change the way you see yourself as a scientist? Do you tend to focus more on translation when asking questions now?

00;28;14;02 – 00;28;43;13

Tony

I mean, I’m really a basic discovery scientists, and I haven’t really ever done anything translational. I mean, what we did led to translational work, and in fact, we didn’t patent any of these original discoveries. It really wasn’t common for biologists to patent things. And so in principle, you know, we could have thought and, I guess we did, that

00;28;43;13 – 00;29;14;22

Tony

maybe if you could target these kinases, that would be a potential treatment. But we didn’t have any experience in how to do that. And, you know, that depended on companies. There’s been much more emphasis now on being translational. Most applications now require to say something about how what you’re discovering or would discover with funding could be translated. So really, very little of what has gone on in my lab has been translational.

00;29;14;22 – 00;29;36;05

Tony

It’s been sort of more blue sky discovery type research, hoping to find something new and interesting. And, you know, the work on histidine phosphorylation that we’ve been doing for the last few years really wasn’t originally intended to be translational. It was just to try to understand how this new or different type of protein phosphorylation is used in cells.

00;29;36;07 – 00;30;08;07

Tony

Ultimately, it may lead to something, but it was nothing immediately on the horizon. The two cancers we have focused on, particularly pancreatic cancer, where we did hope that what we were doing might be translated. And our work on secreted proteins mediate crosstalk between different cell types in pancreatic cancer led to the discovery that this leukemia inhibitory factor, or LIF cytokine, could be potentially targeted and, not through our work,

00;30;08;07 – 00;30;36;14

Tony

but a small company developed and that an antibody that neutralizes the LIF cytokine and that has been in clinical trials in pancreatic cancer. And AstraZeneca acquired this antibody a few years ago now. And they’ve run a phase two trial whose results will be revealed shortly, I hope. And then the other cancer is bladder cancer, where we had this recent work on a PIN1, prolyl isomerase, protein,

00;30;36;14 – 00;31;09;10

Tony

which we had discovered, a postdoc in the lab discovered in 1996. And it’s been of interest as a potential cancer target for many years. The PIN1 protein in the cancer cells is important for them to be able to make cholesterol, which they need in order to proliferate and survive. So targeting PIN1 essentially in collaboration, in combination with another drug that also blocks cholesterol synthesis, a statin, is a potential therapeutic avenue there.

00;31;09;12 – 00;31;21;19

Isabella

You’ve been able to see quite a few projects develop over long periods of time. Does seeing that evolution of scientific understanding make you research or ask questions differently?

00;31;21;22 – 00;31;47;21

Tony

Well, I run the lab by allowing postdocs to pick their own projects. They own the project, and they can take it away with them when they leave the lab. And so in the case of PIN1, the postdoc who discovered it, not looking for it specifically, but through studies on another protein kinase that he had worked on as a graduate student–so sometimes postdocs bring projects from their graduate studies.

00;31;47;21 – 00;32;07;02

Tony

He stumbled on on PIN1 and showed it was important in in cell proliferation. And then he went off to Harvard to be an assistant professor, and he took the project with him. So basically, we didn’t do very much more on PIN1 until Xue Wang came to the lab and said she wanted to work on PIN1, and I said, that’s great.

00;32;07;02 – 00;32;23;03

Tony

We haven’t worked on it for a while. And she said, I want to work on it in bladder cancer. And we’d never worked on bladder cancer. And so really, the credit goes to her for having decided this was going to be an important target protein in bladder cancer. And she really spearheaded the work on this project by herself.

00;32;23;05 – 00;32;26;02

Isabella

What made you decide to run your lab that way?

00;32;26;04 – 00;32;50;28

Tony

I was sort of brought up in science that Asher Korner, my thesis advisor, had basically, he had nine students in the lab, he basically said, go find something interesting to do. So I pretty much did my graduate project independently. And so having had that experience, I felt, you know, that was a good way to to get the best out of people was to let them find something that they were really passionate about.

00;32;50;28 – 00;32;57;26

Tony

And then then they would put more effort into it, and they could take it with them if they wanted to go to an academic position.

00;32;57;29 – 00;33;03;04

Isabella

Related to that as well, do you have any other specific ways you like to establish culture in your lab?

00;33;03;09 – 00;33;22;22

Tony

Well, as I say, I encourage people to find their own projects and they can either pick up something that was left behind by another postdoc or person, or they can come up with something totally novel. You know, people come to the lab because they’re interested in the general area of phosphorylation or translational modification, ubiquitination, simulation. And so there’s a natural sort of affinity between their interests.

00;33;22;22 – 00;33;38;12

Tony

And so very often the collaborations arise within the lab that really sort of strengthens the project. And while they may have their own individual projects, they collaborate with other people for specific areas in specific, you know, parts of the project.

00;33;38;15 – 00;33;41;04

Isabella

Do you collaborate with other faculty yourself?

00;33;41;10 – 00;33;53;24

Tony

We have collaborated with many faculty. I think I said 45 faculty members and I have had our names on the same paper, as it were. It’s been, you know, a great strength, I think, of both the Institute and my own work.

00;33;53;27 – 00;34;03;21

Isabella

Facilitating close relationships and collaboration was a huge goal in the founding and design of Salk. Do you think in practice that the Institute accomplishes that?

00;34;03;24 – 00;34;24;26

Tony

Absolutely, yes. No, I think we we encourage it when we recruit new people, particularly junior level people, one of the things we think about is will have, you know, will they be collaborative? Will they interact? How well will they interact with other people? Will they take advantage of the fact that, you know, we have all this expertise here that would allow them to move and branch out in a new direction?

00;34;24;28 – 00;34;43;04

Tony

In fact, I often tell people as they start out that, while they’ve been recruited to work on what they have been doing as a postdoc, I expect them within a few years to be working on something totally different because of the environment and influence of other people here.

00;34;43;04 – 00;34;48;04

Isabella

Is there anything specific you look for when interviewing new faculty?

00;34;48;06 – 00;35;14;07

Tony

I think the most telling thing is, is the chalk talk. They all always give very professional interview seminars, right? On the work they’ve been doing. But it’s when they have to sit in a room with 20 or 30 other faculty members grilling them about what, you know, what their plans and what they’re proposing to do, how well they cope with that environment and how quickly they think on their feet.

00;35;14;07 – 00;35;27;17

Tony

I think that’s probably the most important, and particularly if they, if they’re really good, they will say spontaneously, I think I can collaborate with X or Y on this particular aspect of my projects, and they’ve done their work. I think that’s always a good sign.

00;35;27;20 – 00;35;34;27

Isabella

I’m so curious culturally, what things do you think have changed the most and the least at Salk since you started 50 years ago?

00;35;34;29 – 00;36;05;09

Tony

When I started, it was really a small institution. There were only a couple of hundred people here. We were all with one exception in the North building, and so there was a lot more interaction. I think now people are a little more siloed between the North and the South building and the East building. We don’t spontaneously see them in the way that we used to. I mean there are ways through which people interact, you know, faculty the month talk is is one way that you can find out what your colleagues are doing.

00;36;05;09 – 00;36;22;11

Tony

Faculty lunch, all that sort of smaller, smaller meetings is a way that people can interact. You know, you won’t collaborate unless you know what someone else is doing.

00;36;22;13 – 00;36;25;08

Isabella

You’ve won many awards.

00;36;25;11 – 00;36;26;08

Tony

All for the same thing.

00;36;26;08 – 00;36;39;03

Isabella

I’m curious, though, has there been a milestone or award or a thing that happened in your career that anyone else would probably think is silly, but you found particularly meaningful or special?

00;36;39;05 – 00;37;05;14

Tony

If you look at my office door, you’ll see the occasion when I was mock-knighted by Jamie Simon dressed up as Queen Elizabeth the First. And the sword is still hanging over my door that he made for this occasion. That was pretty surprising. Yeah, other important things in my life. Obviously our kids, our two sons, our son has just got an assistant professorship at UCLA, so I’m very proud of him.

00;37;05;14 – 00;37;29;05

Tony

And yeah, so my family has been really important in supporting me. That’s not a single occasion, I must admit. But perhaps the most unusual one was the the surfing award that you UCSD gives out. I get what they call it, it’s the Queen Maha Surfing award. That’s just a picture with a surfboard on it. That was that was pretty unusual.

00;37;29;11 – 00;37;36;16

Isabella

Something else I’ve heard that is quite meaningful to you is your t-shirt collection. That’s your real legacy.

00;37;36;19 – 00;38;05;18

Tony

Yes. I have a huge collection. It’s something close on 400 now, which my wife despairs of because they’re taking out so much shelf space in the in, in our closet– closets, actually. I think it probably started with river trip t-shirts actually. I have river trip t-shirts going back to the 70s. First meeting t-shirts would have been in the 80s, a lot of them designed by by Jamie Simon.

00;38;05;18 – 00;38;34;24

Tony

The poster on the wall outside my office on the left hand side is all of the cartoons he did for abstract book covers for the oncogene meeting that I started with George Vande Woude in 1985. So, and then he’s done t-shirts for all the Salk meetings that I’ve organized. But t-shirts are gone out of fashion. People really don’t– meetings don’t give out t-shirts anymore.

00;38;34;26 – 00;38;37;27

Tony

Which is sort of sad. Yeah. Anyway, that’s the way it is.

00;38;37;29 – 00;38;39;20

Isabella

Do you wear a different t-shirt every day?

00;38;39;26 – 00;38;40;22

Tony

I have favorites.

00;38;40;22 – 00;38;44;08

Isabella

Don’t think you could have gotten away with t-shirts every day back in Cambridge.

00;38;44;14 – 00;39;07;09

Tony

Certainly not, I would never. You know, I didn’t wear ties, but I did wear–often had a kerchief when I was a student. Things have got less formal there anyway. I mean, used to be you had to wear a tie to to dinner in hall when you were an undergraduate, and your gown. So when I came back so I was, I said, a fellow of Christ College, a formal occasion.

00;39;07;12 – 00;39;18;00

Tony

You eat at High Table, which is on a platform at ten inches above the rest of the hall, and that the undergraduates sit on tables that are length down the length of the hall, and the high table is across the top.

00;39;18;03 – 00;39;18;15

Isabella

Just like Hogwarts.

00;39;18;15 – 00;39;45;01

Tony

Just like Hogwarts, exactly like Hogwarts, which was shot in Oxford, as you know. And so the fellows come in wearing gowns. You have to wear a gown, as well. And so when I came back from California, I’d grown my beard obviously, I looked definitely– didn’t look like a fellow. And I had made some macrame headbands to keep my hair under control.

00;39;45;01 – 00;39;58;22

Tony

And so I would go and, I would go and dine in hall wearing a macrame headband. They didn’t say anything! But that, I did it, so. I didn’t wear t-shirts to hall.

00;39;58;25 – 00;40;07;18

Isabella

I feel like that is a perfect way to summarize your style and your attitude and your intellect all at once, so I’ll end there. Thank you so much, Tony.

00;40;07;20 – 00;40;13;13

Tony

Thank you.

00;40;13;15 – 00;40;46;06

Isabella

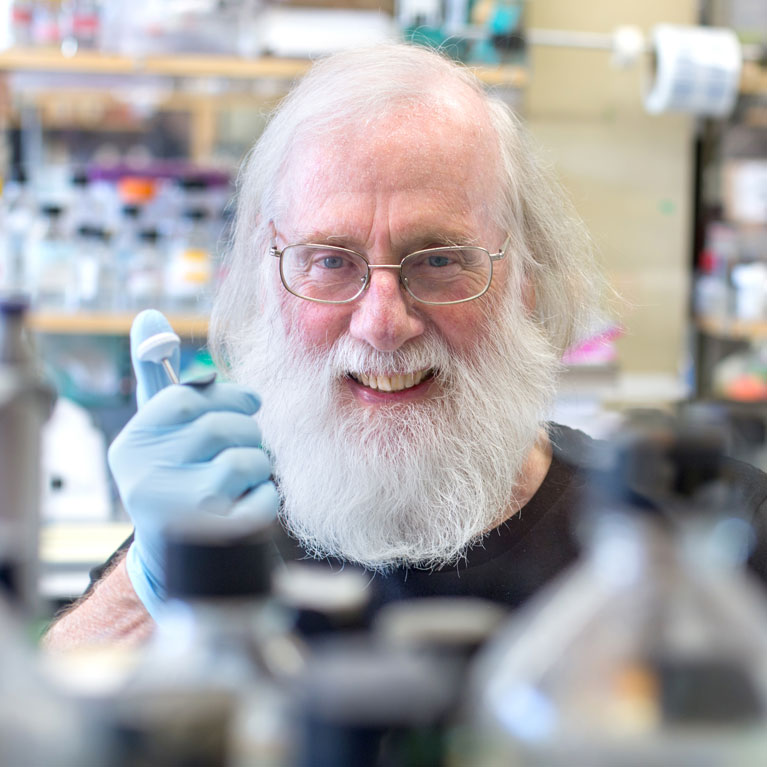

Tony Hunter is truly a force whose impact goes beyond the translation of his findings. By supporting the curiosity of fledgling scientists as they come through his lab, his impact expands exponentially. As he mentors, his mentees become mentors, and on and on, he shapes generations of cancer biologists. After 50 remarkable years of discovery and countless awards and honors, Tony still enters the room and a graphic tee, flip flops, and iconic white beard, ready to talk science and recollect memories from inside and outside the lab.

00;40;46;09 – 00;41;13;10

Isabella

Thankfully, he’s still making more memories in his well-loved Salk office, where he sits surrounded by a lifetime of books and papers. There, amongst his incredible archive, he stays curious and engaged, seeing discoveries through yesterday, today, and tomorrow. He’s already changed the field of cancer biology enormously. Who’s to say what he’ll find next?

00;41;13;13 – 00;41;43;27

VO Victoria

Beyond Lab Walls is a production of the Salk Office of Communications. To hear the latest science stories coming out of Salk, subscribe to our podcast, and visit Salk.edu to join our new exclusive media channel, Salk Streaming. There, you’ll find interviews with our scientists, videos on our recent studies, and public lectures by our world renowned professors. You can also explore our award winning magazine, Inside Salk, and join our monthly newsletter to stay up to date on the world within these walls.