May 2, 2016

Salk study is first to closely follow development of new neurons in the adult brain, giving potential insight into neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism and schizophrenia

Salk study is first to closely follow development of new neurons in the adult brain, giving potential insight into neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism and schizophrenia

LA JOLLA—When tweaking its architecture, the adult brain works like a sculptor—starting with more than it needs so it can carve away the excess to achieve the perfect design. That’s the conclusion of a new study that tracked developing cells in an adult mouse brain in real time.

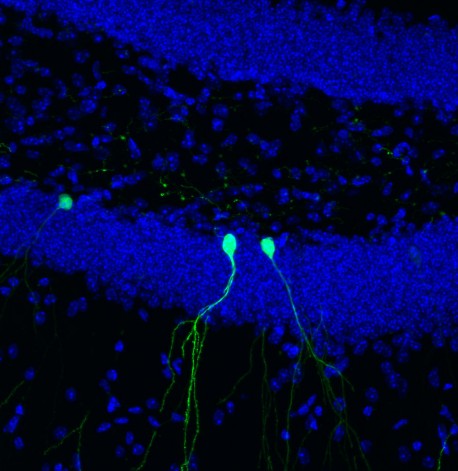

Click here for a high-resolution image

Credit: Salk Institute

New brain cells began with a period of overgrowth, sending out a plethora of neuronal branches, before the brain pruned back the connections. The observation, described May 2, 2016 in Nature Neuroscience, suggests that new cells in the adult brain have more in common with those in the embryonic brain than scientists previously thought and could have implications for understanding diseases including autism, intellectual disabilities and schizophrenia.

“We were surprised by the extent of the pruning we saw,” says senior author Rusty Gage, a professor in Salk’s Laboratory of Genetics and holder of the Vi and John Adler Chair for Research on Age-Related Neurodegenerative Disease.

While most of the brain’s billions of cells are formed before birth, Gage and others previously showed that in a few select areas of the mammalian brain, stem cells develop into new neurons during adulthood. In the new study, Gage’s group focused on cells in the dentate gyrus, an area deep in the brain thought to be responsible for the formation of new memories. The scientists used a new microscopy technique to observe new cells being formed in the dentate gyrus of adult mice.

“This is the first time we’ve been able to image dentate neurons growing in a living animal,” says Tiago Gonçalves, a research associate in the Gage lab and first author of the new paper.

Click here for a high-resolution image

Credit: Salk Institute

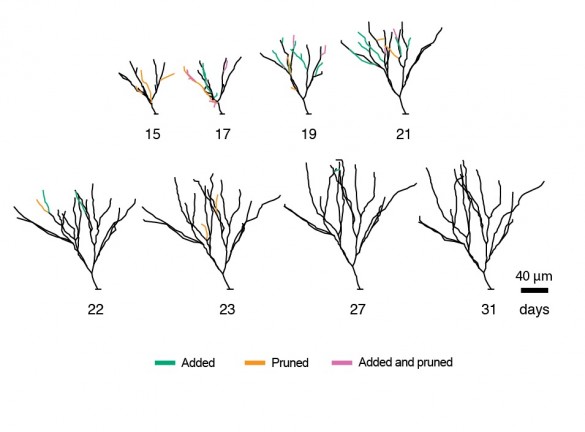

Gonçalves and Gage followed—on a daily basis—the growth of neurons over several weeks. When animal were housed in environments with lots of stimuli—running wheels, plastic tubes, and domes—the new cells grew quickly, sending out dozens of branches called dendrites which receive electrical signals from surrounding neurons. When kept in empty housing, the new neurons grew slightly slower and sent out, on average, a few less dendrites. But, in both cases, the dendrites of the new cells began to be pruned back.

“What was really surprising was that the cells that initially grew faster and became bigger were pruned back so that, in the end, they resembled all the other cells,” says Gonçalves. He and his colleagues went on to show that changing signaling pathways could mimic some of the effects of the complex environment—cells grew more initially, but also pruned back earlier.

Click here for a high-resolution image

Credit: Salk Institute

So why would the brain spend energy developing more dendrites than needed? The researchers suspect that the more dendrites a neuron starts with, the more flexibility it has to prune back exactly the right branches.

“The results suggest that there is significant biological pressure to maintain or retain the dendrite tree of these neurons,” says Gage.

Defects in the dendrites of neurons have been linked to numerous brain disorders including schizophrenia, Alzheimer’s, epilepsy and autism. Charting how the brain shapes these branches—both during embryonic development and in adulthood—may be the key to understanding mental health.

“This also has big repercussions for regenerative medicine,” says Gonçalves. “Could we replace cells in this area of the brain with new stem cells and would they develop in the same way? We don’t know yet.”

Other researchers on the study were Cooper W. Bloyd, Matthew Shtrahman, Stephen T. Johnston, Simon T. Schafer, Sarah L. Parylak, Tranh Tran, and Tina Chang of the Salk Institute.

The work and the researchers involved were supported by grants from The James S. McDonnell Foundation, CIRM, G. Harold & Leila Y. Mathers Charitable Foundation, Annette Merle-Smith, JBP Foundation, NIH and The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust.

JOURNAL

Nature Neuroscience

AUTHORS

J. Tiago Gonçalves, Cooper W. Bloyd, Matthew Shtrahman, Stephen T. Johnston, Simon T. Schafer, Sarah L. Parylak, Tranh Tran, Tina Chang, and Fred H. Gage of the Salk Institute

Office of Communications

Tel: (858) 453-4100

press@salk.edu

Unlocking the secrets of life itself is the driving force behind the Salk Institute. Our team of world-class, award-winning scientists pushes the boundaries of knowledge in areas such as neuroscience, cancer research, aging, immunobiology, plant biology, computational biology and more. Founded by Jonas Salk, developer of the first safe and effective polio vaccine, the Institute is an independent, nonprofit research organization and architectural landmark: small by choice, intimate by nature, and fearless in the face of any challenge.