July 8, 2019

Salk scientists borrowed methods from computer science to

develop new approach

Salk scientists borrowed methods from computer science to develop new approach

LA JOLLA—In the nucleus of every living cell, long strands of DNA are tightly folded into compact chromosomes. Now, thanks to a new computational approach developed at the Salk Institute, researchers can use the architecture of these chromosome folds to differentiate between types of cells. The information about each cell’s chromosome structure will give scientists a better understanding of how interactions between different regions of DNA play a role in health and disease. The study was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences the week of July 8, 2019.

“In a tissue like liver or heart or brain, there are many diverse cell types we don’t understand yet; this is a new tool to help us look at these cells one at a time,” says Salk Professor and Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator Joseph Ecker, who heads Salk’s Genomic Analysis Laboratory.

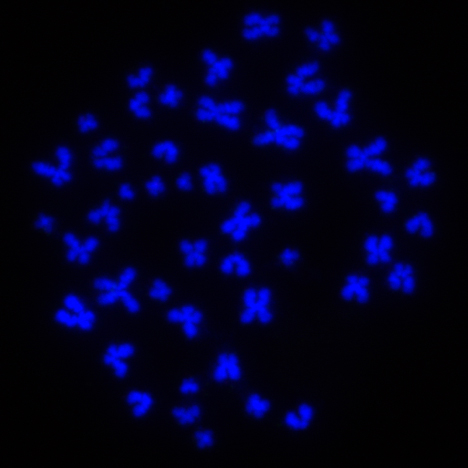

Click here for a high-resolution image.

Credit: Salk Institute

Researchers know that a majority of the human genome is made up of regulatory DNA—stretches of DNA that don’t themselves encode proteins, but help control whether, and when, genes are expressed in any given cell. This regulation may occur through physical interactions between a regulatory stretch of DNA and a gene. Regulatory regions, however, might be far from a gene they regulate on a linear strand of DNA. In the process of chromosome assembly, tight, specific connections are formed between genes and regulatory DNA, held closely together in a folded chromosome.

In 2009, researchers developed Hi-C, a method of probing cells for these chromosomal interactions. Knowing which stretches of DNA physically interact can tell scientists what the effect of a mutation in a regulatory region might be, helping to explain why levels of a protein are altered in a diseased cell. Typically, Hi-C is used on many cells at once and the results capture only an average of the chromosome architecture in a population of cells. This means that if there’s an interaction between two regions of DNA, but it’s only present in a small minority of cells, it won’t show up in a standard Hi-C experiment.

“If half of the cells you’re studying have a particular chromosome architecture, you can see that, but you really can’t tell what individual cells are doing,” says Ecker. His group wanted to develop a way to get more detailed single-cell data from Hi-C experiments.

The problem with applying Hi-C to single cells is that cells of the same type can have variability in their chromosome architecture, says graduate student Jingtian Zhou, first author of the new paper. Moreover, a Hi-C experiment done on a single cell only reveals data on about 5% of the genome. So finding trends—such as concluding that one cell type has a change in chromosome architecture when disease is present—is tricky. But it turns out that those two problems with the data—known as heterogeneity and sparsity—are dealt with by researchers in many diverse fields that have to analyze large data sets, and there are some solutions.

“We ended up borrowing algorithms used in computer science and applying them to biological data to help us deal with the sparsity and heterogeneity of single-cell Hi-C results,” says Zhou.

With this inspiration from computer science, the team developed scHiCluster, an algorithm to sift through Hi-C data from mixed cells and sort the cells into discrete groups based on the similarity of their chromosome interactions. That lets them more easily draw conclusions about what cells are doing when it comes to gene regulation in different biological circumstances.

They tested the algorithm on previously published sets of Hi-C data, showing that they could correctly sort out different cell types from a mixed dataset. The new approach will come in handy as researchers continue to study how cells in the human body function, and how that function goes awry in disease.

“If you take a disease like Alzheimer’s, researchers have found changes in gene expression in some brain cell types,” says Ecker. “But until now, we didn’t have the ability to easily link those gene expression changes to regions in the genome that control gene transcription.”

The group plans to generate Hi-C data in single cells in a variety of human tissues. Applying the computational technique to studying single-cell chromosome structures could further facilitate the understanding of gene regulation diversity in different cells types.

Other researchers on the study were Yusi Chen, Terrence Sejnowski and Jesse Dixon of the Salk Institute; Jianzhu Ma, Chuankai Cheng and Bokan Bao of UC San Diego; and Jian Peng of University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

The work described in this paper was supported by the National Human Genome Research Institute.

DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1901423116

JOURNAL

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

AUTHORS

Jingtian Zhou, Jianzhu Ma, Yusi Chen, Chuankai Cheng, Bokan Bao, Jian Peng, Terrence J. Sejnowski, Jesse R. Dixon, and Joseph R. Ecker

Office of Communications

Tel: (858) 453-4100

press@salk.edu

Unlocking the secrets of life itself is the driving force behind the Salk Institute. Our team of world-class, award-winning scientists pushes the boundaries of knowledge in areas such as neuroscience, cancer research, aging, immunobiology, plant biology, computational biology and more. Founded by Jonas Salk, developer of the first safe and effective polio vaccine, the Institute is an independent, nonprofit research organization and architectural landmark: small by choice, intimate by nature, and fearless in the face of any challenge.