December 24, 2015

Salk discovery of novel pathway could be a boon to agriculture

Salk discovery of novel pathway could be a boon to agriculture

LA JOLLA—Despite seeming passive, plants wage wars with each other to outgrow and absorb sunlight. If a plant is shaded by another, it becomes cut off from essential sunlight it needs to survive.

To escape this deadly shade, plants have light sensors that can set off an internal alarm when threatened by the shade of other plants. Their sensors can detect depletion of red and blue light (wavelengths absorbed by vegetation) to distinguish between an aggressive nearby plant from a passing cloud.

Scientists at the Salk Institute have discovered a way by which plants assess the quality of shade to outgrow menacing neighbors, a finding that could be used to improve the productivity of crops. The new work, published December 24, 2015 in Cell, shows how the depletion of blue light detected by molecular sensors in plants triggers accelerated growth to overcome a competing plant.

“With this knowledge and discoveries like it, maybe you could eventually teach a plant to ignore the fact that it’s in the shade and put out a lot of biomass anyway,” says Joanne Chory, senior author and director of Salk’s Plant Molecular and Cellular Biology.

Ullas V. Pedmale and Joanne Chory

Click here for a high-resolution image.

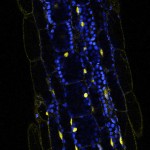

Image: Courtesy of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies

The new work upends previously held notions in the field. It was known that plants respond to diminished red light by activating a growth hormone called auxin to outpace its neighbors. However, this is the first time researchers have shown that shade avoidance can happen through an entirely different mechanism: instead of changing the levels of auxin, a cellular sensor called cryptochrome responds to diminished blue light by turning on genes that promote cell growth.

This revelation could help researchers learn how to modify plant genes to optimize growth to, for example, coerce soy or tomato crops (which are notoriously fickle) grow more aggressively and give a greater yield even in a crowded, shady field.

The focus of the team’s research efforts was cryptochromes, blue light-sensitive sensors that are responsible for telling a plant when to grow and when to flower. Cryptochromes were first identified in plants and later found in animals, and in both organisms they are associated with circadian rhythm (the body’s biological clock). The protein’s role in sensing depletion of blue light had been known, but this study is the first to show how cryptochromes promote growth in a shaded environment.

The team placed normal and mutant Arabidopsis plants in a light-controlled room where blue light was limited. The mutant plants lacked either cryptochromes or a PIF transcription factor, a type of protein that binds to DNA to control when genes are switched on or off. PIFs typically make direct contact with red light sensors, called phytochromes, to initiate shade avoidance growth. The researchers compared the responses of the mutant and normal plants in the varying blue light conditions by monitoring the growth rate of the stems and looking at contacts between cryptochromes, PIFs and chromosomes.

“We found that cryptochromes contact these transcription factors on DNA, activating genes completely different than what other photoreceptors activate,” says Ullas Pedmale, first author of the work and a Salk research associate. “This is also a very short pathway so plants can rapidly respond to their light environment.”

The next step for the work is to understand how to manipulate the growth response. “Ultimately, we could help farmers grow crops very close together by changing how plants put out leaves, how fast the leaves grow and at what angles the leaves grow relative to each other and the stem. This will help increase yield in the next few generations of crop plants,” says Chory, who is also a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator and holds the Howard H. and Maryam R. Newman Chair in Plant Biology.

“Shade avoidance and the response of plants to increases in temperature look similar and in fact share many common molecular components,” adds Pedmale. “Therefore, studying shade avoidance will not only lead to increases in yield in shaded environments, but may explain how to increase yield in a warming climate.”

Other authors on the paper were Shao-shan Carol Huang, Mark Zander, Benjamin Cole, Jonathan Hetzel, Pedro Reis, Kazumasa Nito, Joseph Nery and Joseph Ecker of the Salk Institute; Karin Ljung of the Umeå Plant Science Centre in the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences; and Priya Sridevi of the University of California, San Diego.

The work was supported by the NIH, Rose Hills Foundation, the H.A. and Mary K. Chapman Charitable Trust, DOE, the NSF, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

JOURNAL

Cell

AUTHORS

Ullas V. Pedmale, Shao-shan Carol Huang, Mark Zander, Benjamin J. Cole, Jonathan Hetzel, Karin Ljung, Pedro A. B. Reis, Priya Sridevi, Kazumasa Nito, Joseph R. Nery, Joseph R. Ecker and Joanne Chory

Office of Communications

Tel: (858) 453-4100

press@salk.edu

Unlocking the secrets of life itself is the driving force behind the Salk Institute. Our team of world-class, award-winning scientists pushes the boundaries of knowledge in areas such as neuroscience, cancer research, aging, immunobiology, plant biology, computational biology and more. Founded by Jonas Salk, developer of the first safe and effective polio vaccine, the Institute is an independent, nonprofit research organization and architectural landmark: small by choice, intimate by nature, and fearless in the face of any challenge.