October 17, 2011

Scientists' discovery of new form of neonatal respiratory distress syndrome offers clues to treatments for infants who don't respond to steroid drugs

Scientists' discovery of new form of neonatal respiratory distress syndrome offers clues to treatments for infants who don't respond to steroid drugs

LA JOLLA, CA—A discovery by scientists at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies might explain why some premature infants fail to respond to existing treatments for a deadly respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) and offers clues for new ways to treat the breathing disorder.

The scientists identified a new form of RDS in newborn mice and traced the problem to a cellular receptor for thyroid hormone, a key player in many developmental processes in the body. They found that two drugs used for treating overactive thyroid glands saved mice with a deadly genetic alteration that mimicked the newly discovered lung problem.

“We’ve added a piece of the puzzle that had been missing for decades,” says Ronald Evans, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator and the March of Dimes Chair in Developmental and Molecular Biology at Salk. “This gives us an entirely new avenue for explaining and treating RDS and other respiratory problems that occur in infants.”

Ronald Evans and Liming Pei

Image: Courtesy of Salk Institute for Biological Studies

RDS affects about one percent of infants born in the United States and is the leading cause of death among premature babies. The disease occurs because the infants’ lungs are not yet fully developed at birth and lack a slippery substance called surfactant, which is necessary for the lungs to inflate with air.

To encourage the lungs to develop faster and produce the surfactant, doctors treat many expecting mothers and premature infants with glucocorticoids, steroid drugs that speed maturation of surfactant-producing cells, known as type 2 pneumocytes.

In some cases, however, infants fail to respond to the steroid treatment, and die from the respiratory syndrome, which suggests that some other biological mechanism might be at work.

To explain this, the Salk researchers turned their attention to another type of cell lining the lungs, type 1 pneumocytes, flat cells that allow air exchange between the blood stream and the lung’s interior.

“We knew that both types of cells, type 1 and type 2 pneumocytes, would be important for lung development, ” says Liming Pei, a postdoctoral research associate who led the project. “While a lot is known about type 2 cells, the type 1 cell is poorly understood.”

The researchers developed a strain of mice in which they disrupted the ability of type 1 pneumocytes to respond normally to thyroid hormone, which prevented the cells from maturing.

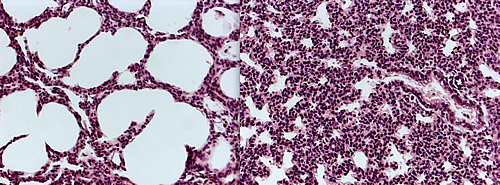

These microscopic images of lung tissue from newborn mice show a cross section of the alveoli, the buds in lungs where air exchange takes place. The air sacs (white) in the alveoli on the left, which were taken from a normal mouse, have expanded fully, indicating the animal could breath normally. Those on the right have failed to expand, because the mouse suffered from a new respiratory syndrome discovered by Salk scientists.

Image: Courtesy of Salk Institute for Biological Studies

Unlike type 2 pneumocytes, which mature rapidly in infants given steroid hormone, the type 1 cells failed to respond to steroid treatment and the mice died due to the inability of their lungs to function.

However, mice treated with the medications propylthiouracil or methimazole, normally given to people with thyroid disease, recovered from the disorder and their type 1 cells matured normally.

“This might explain why some infants don’t respond to steroid treatment, which only targets the type 2 pneumocytes,” Evans says. “There may be an entirely different underlying problem than what the doctor is treating.”

The findings identify cell sensors (called thyroid hormone receptors) that help type 1 pneumocytes mature and suggest that drugs controlling this hormone could help premature infants’ lungs function earlier.

The genetic make up of mice and humans is very similar, so the researchers are optimistic that their findings will eventually lead to new treatments for infants with RDS. “These mechanisms could also play a role healing lung tissues,” Pei says. “They might help older children and adults who have suffered lung damage from flu, asthma, emphysema or other types of respiratory disorders.”

He cautioned, however, that the thyroid drugs used in the study are only approved for adults, and that their use in infants would have to be explored with caution. However, because their properties are well known there is clear potential for their use in infants.

The findings of the research, which was funded by the Francis Family Foundation, the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust, the March of Dimes and the National Institutes of Health, was published in Nature Medicine.

About the Salk Institute for Biological Studies:

The Salk Institute for Biological Studies is one of the world’s preeminent basic research institutions, where internationally renowned faculty probe fundamental life science questions in a unique, collaborative, and creative environment. Focused both on discovery and on mentoring future generations of researchers, Salk scientists make groundbreaking contributions to our understanding of cancer, aging, Alzheimer’s, diabetes and infectious diseases by studying neuroscience, genetics, cell and plant biology, and related disciplines.

Faculty achievements have been recognized with numerous honors, including Nobel Prizes and memberships in the National Academy of Sciences. Founded in 1960 by polio vaccine pioneer Jonas Salk, M.D., the Institute is an independent nonprofit organization and architectural landmark.

For more information:

Nature Medicine

Authors: Liming Pei, Mathias Leblanc, Grant Barish, Annette Atkins, Russell Nofsinger, Jamie Whyte, David Gold, Mingxiao He, Kazuko Kawamura, Hai-Ri Li, Michael Downes, Ruth T Yu, Henry C Powell, Jerry B Lingrel & Ronald M Evans

Thyroid hormone receptor repression is linked to type I pneumocyte-associated respiratory distress syndrome

Office of Communications

Tel: (858) 453-4100

press@salk.edu