Explore Salk – Architecture Guide

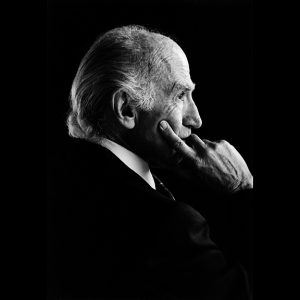

The Salk Institute for Biological Studies is an independent, nonprofit research organization and architectural landmark founded in 1960 by Jonas Salk, developer of the first safe and effective polio vaccine. The construction of the building was funded by March of Dimes and is located on 27 acres of land overlooking the Pacific Ocean gifted to Salk by the City of San Diego. Construction of the Salk Institute began in 1962.

Inspired to rid humanity of polio, he used basic science to solve its mysteries and, in the process, helped alter the course of the 20th century—and the future of science, medicine, and human health. His story doesn’t end there. Neither have the benefits of his vision and work.

Salk dreamed of creating a collaborative environment where scientists could explore the basic principles of life and realize the broader implications of their discoveries for the future of humanity.

Today, a new generation of world-class, award-winning scientists pushes the boundaries of knowledge in areas such as neuroscience, cancer research, aging, immunobiology, plant biology, computational biology, and more.

Design Collaboration

Salk enlisted world-renowned architect Louis Kahn to design and build the Institute with his vision of creating large, open, and unobstructed laboratory spaces capable of evolving with the changing needs of science, while withstanding the tests of time—all while being a place “worthy of a visit by Picasso.”

The design collaboration of Jonas Salk and Louis Kahn produced one of the most architecturally renowned sites in the world, an homage to science set in concrete, teak, and marble that still serves as both an inspiration and a workplace for innovative leaders in the biological sciences.

➊ “The Sun” by Dale Chihuly

The Salk Institute celebrated its 50th anniversary with Chihuly at the Salk, an outdoor exhibit featuring blown-glass installations by renowned American glass artist Dale Chihuly. One of the pieces, “The Sun,” generously donated by Joan and Irwin Jacobs, is a representation of the union of art and science that has been intertwined with the Institute’s history.

➋ Eucalyptus Grove

Originally planted at the turn of the 20th century to provide lumber for the growing City of San Diego, the tall eucalyptus trees (which were ultimately deemed unsuitable for building material) provide a natural setting for the approach to the labs. Inspired by the Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi, a monastery in the mountains of Italy, Kahn envisioned visitors wandering through the grove, discovering the secluded lab buildings as one would encounter a ruin, castle, or monument—timeless and aging naturally.

➌ Orange Grove

Through the Corten steel gate (purposely oxidized), one passes from the boundary of a natural environment to a more ordered one. Orange trees are planted in a grid pattern, symbolizing a cultivated garden that acts as the site of the origin of knowledge in many philosophies and religions.

➍ North and South Buildings

Louis Kahn’s creation consists of two mirror-image structures that flank a grand courtyard. Each building is six stories (three floors are below ground) and contains original laboratory space. The structures are made of concrete, teak, lead, glass, and special steel. Close attention was paid to the forms for the concrete walls, which were made of ¾-inch exterior plywood, filled, sanded, and finished with coats of polyurethane resin. By only using the forms a few times before refinishing, the concrete cured to a smooth, marble-like surface. The poured-in-place concrete walls create a bold first impression for visitors.

Kahn drew inspiration from Roman times to rediscover the waterproof qualities and the warm, pinkish glow of “pozzolanic” concrete. Kahn deliberately chose to accentuate the joints between the concrete panels, chamfering the edges to produce a V-shape groove at the joints along the wall surfaces. Even the spacing of the form ties, the small circles seen speckling the concrete, were carefully considered, and filled with lead plugs.

Once the concrete was set, he allowed no further processing of the finish—no grinding, no filling, and above all, no painting. The architect chose an unfinished look for the teak surrounding the study towers and west office windows, and he directed that no sealer or stain be applied.

The Institute has 2,352 solar panels on the roof of the buildings that supply 500 kilowatts of energy per year.

➎ Laboratories

By separating floors that contained lab spaces and offices from ones that contained electricity, ventilation, and other utilities, Kahn’s design enabled the Institute’s remarkable flexibility. The lack of walls between laboratories drives a spirit of collaboration and allows for adaptation to the ever-changing needs of science.

Coastal zoning codes restricted the height of the buildings, so some laboratories had to be underground. Kahn thoughtfully designed a series of light wells 40 feet long and 25 feet wide on both sides of each building and built steel storefront windows to flood each laboratory with daylight and views.

➏ Courtyard

The focal point of the Salk Institute is the Courtyard nestled between the two mirror-image lab buildings. It is a single expanse of open space and a unifying area for social interaction. While Kahn had anticipated planting trees and other greenery in the Courtyard, he collaborated with contemporary Mexican architect Luis Barragán, who stated, “I would not put a tree or blade of grass in this space … If you make this a plaza, you will gain a façade—a façade to the sky.”

The Courtyard is enclosed on both long sides by the laboratories, in front of which lofty study towers give a remarkable depth through the layering of space, an effect unknown in traditional collegiate courts.

The sheltered porticos below the towers meet Jonas Salk’s brief that “cloisters” should be brought to the laboratories. This results in myriad vistas in all directions.

➐ River of Life

A narrow channel cuts into the travertine and runs parallel to the two buildings, flowing east to west carrying a slow-running flow of reclaimed water. For Kahn and Jonas Salk, this canal and fountain, dubbed the “River of Life,” not only recalled the Alhambra at Granada, but also were symbolic of the constant stream of scientific discovery emerging from the labs and progressing out into the greater ocean of humanity’s knowledge.

The Institute was designed so that the sun sets along the axis of the “River of Life” twice a year, on the spring and fall equinoxes.

A 250,000-gallon underground cistern collects rainwater to replenish the “River of Life” and is just one facet of the Institute’s sustainability practices.

➑ Studies

Flanking the Courtyard are individual towers that provide space for 36 private studies lined with teak panels for Salk’s principal investigators. Their articulation as mostly freestanding elements symbolizes their independence from the work in the laboratory.

The towers at the east end of the buildings contain heating, ventilating, and other support systems. At the west end, six floors of offices and solar panels—the Institute has 2,352 solar panels that supply 500 kilowatts of energy per year. The saw-toothed arrangement of the buildings allows for full views of the ocean and plaza.

➒ Red Brick Courtyard and East Building

Upon entering, today’s visitors travel west through a red brick courtyard, added in 1995 and designed by former Kahn associates who worked on the construction of the original campus (David Rinehart and Jack McAllister of Anshen + Allen in Los Angeles). The 110,000-square-foot building has north and south wings, providing much-needed research space, offices, and a scientific meeting center that includes the 300-seat Conrad T. Prebys Auditorium.

For uniformity, and in consideration of the coastal environment, the materials of the new building mimic the original structures thanks to smooth, stone-like concrete, mill-finished stainless steel, and glass. In 2012, a $28 million infrastructure program was completed, upgrading the central plant and other essential operating systems.

[aesop_gallery id=”20808″ revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Architectural Preservation

Fifty years after the buildings’ construction began, their signature teak succumbed to weather, wear, and a fungal infection. In the summer of 2017, the Institute unveiled the successful results of a multi-year effort to preserve the teak window systems of the nearly 60-year-old modernist structure. The $9.8 million project was conducted in partnership with the Getty Conservation Institute and is expected to extend the life of the wood for another 50 to 70 years. That October, the restoration efforts were recognized with an award for Excellence in Craftsmanship and Preservation Technology by the California Preservation Foundation. The Institute shared the honor with Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc., the architectural firm that headed the project.

Today, the Institute is focused on additional conservation efforts, such as concrete repair, needed to maintain other aspects of the structure.

More than 60 years after their construction, the Institute’s buildings continue to be heralded around the globe as architectural and functional icons. Salk’s Architecture Conservation Program is a key part of the Institute’s efforts to preserve the brilliance of Jonas Salk’s vision and the beauty of Louis Kahn’s masterwork for generations to come by supporting the Architectural Conservation Program.

Jonas Salk Changed the World

Inspired to rid humanity of polio, he used basic science to solve its mysteries and, in the process, helped alter the course of the 20th century—and the future of science, medicine, and human health. His story doesn’t end there. Neither have the benefits of his vision and work.

Salk dreamed of creating a collaborative environment where scientists could explore the basic principles of life and realize the broader implications of their discoveries for the future of humanity. In 1960, he founded the Salk Institute for Biological Studies.

Unlocking the secrets of life itself remains the driving force behind the Salk Institute. Salk scientists ask big questions and take risks as they pursue discoveries to remedy some of the most challenging problems of our time, and ultimately make our world a healthier place. We invite you to join us. www.salk.edu/donate >>

Links

Learn more about the Conduct Policy >>